History

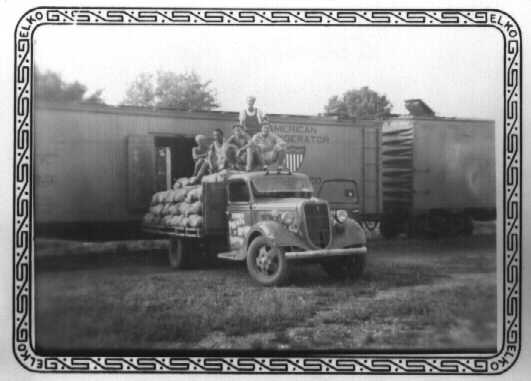

POWs loading sacks of potatoes onto a train near Independence, Missouri. 1944.

It is amazing how few people remember . . .

In most cases, it is only those who were there – as workers in the camps, or farmers who hired on the POWs as field help. Or maybe they were little then, small enough that they remember only the sight of the fences set back from the road, or the sounds of voices speaking in a language they didn’t understand. Perhaps they just remember holding on to a grown-up’s hand as the men in the uniforms marched by on their way to a work assignment.

Indeed, it is mostly just those who were there that are aware of this amazing chapter of history. A time when 15,000 enemy prisoners of war were sent to Missouri. A time when camps surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by watchtowers and patrolling dogs dotted the landscape. When captured labor – Germans and Italians – replaced in the fields the men who had been sent to war, picking cotton, detasseling corn, digging potatoes.

Paul Markl, a German POW, was held at Camp Clark in Nevada, Missouri. He made this sketch of camp life while at the branch camp in Orrick, Missouri, east of Kansas City.

In Hollywood and in literature, prisoner-of-war camps with their fences and guard towers are uniformly miserable places. Not so for those in Missouri and elsewhere in the US. Sure, the men in the camps would rather have been with their families back home in Germany or Italy, but they knew that was not possible. And in truth, many were well aware that their present condition, the main challenge of which was staving off the unrelenting boredom, was infinitely better than their fellow soldiers still at the front. They had plenty to eat, warm clothes and bed, and some opportunity toward education and recreation. Plus the men were paid for the work that they performed in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

The people of the towns where these camps were placed remember too the initial feelings of unease and uncertainty they felt when they learned that the government had decided to put large numbers of “aliens” in their area.

One anonymous writer sent a letter to the War Department in July 1942 expressing his concerns about the plan to establish a large camp in Ste. Genevieve County near Weingarten, Missouri:

TO THE WAR DEPARTMENT:

Of all the ridiculous things done by the U. S. A. before and after December 8, 1941, this takes the prize:

WEINGARTEN, MO., SELECTED FOR ALIEN INTERNMENT CAMP.

Weingarten, town of 99 inhabitants in Ste. Genevieve County, Mo., 75 miles south of St. Louis, has been selected by the War Department as the site of an internment camp for aliens.”

So reads today’s Post Dispatch.

Doesn’t anyone in Washington know that Ste. Genevieve County, Missouri, is as german as Germany, and that putting an alien enemy camp there is about as safe as putting it in Berlin? The people down there, many of whom have been here for several generations, speak English with a german accent that can be cut by a knife or don’t speak English at all — German is still their mother-tongue, and Germany is still their Fatherland. By putting an alien enemy camp down there you are simply inviting escapes, which will be winked at by the natives, and the aliens can find refuge with their hun friends in St. Louis, Cincinnati and Milwaukee. That dutch town is full of germans who are indignant at Japan, but hold nothing against Germany.

Better put your camp near Lidice, Ill., or some other place not adjacent to such german centers at St. Louis, Cincinnati and Milwaukee. Or, if you MUST put it at Weingarten (even the name of the town is german) for political purposes, then for heaven’s sake put only Japs in it, or even Italians might be safe there, but keep the huns out or you’ll have to keep an army down there to keep the huns from escaping with the aid of their S. E. Missouri friendly enemies.

AMERICA FIRST AND ALWAYS.

While the letter above was likely written for effect rather than actual sentiment, the people of these small towns were concerned, of course, wondering to some extent about their safety. They were also worried about the influx of army personnel that accompanied such an operation, and the way all of those people might change their town. Suddenly there were housing shortages as well as the strain on relations with the government when the land for the camps were initially taken from people who had in some cases farmed it for generations.

But by and large this turned out to be a pleasant time for those involved, whether prisoner, guard or local resident. As it happens with people, life fell into a rhythm of days and nights, work and rest – even if it was done while confined behind a fence. Friendships sometimes developed between prisoners and the guards as well as between prisoners and the people who were helped by their labor.

This is the story of how 15,000 men came suddenly to Missouri, taken from fighting a half a world away. They came as our enemy, but in many cases they left as friends, or at the least, with a more positive view of the United States. They worked here and lived here, and just as quickly, were gone again, in most cases leaving nothing more behind than memories with those who resided nearby or worked in the camps.